A hill of crowns and chapters

Courtyards, chapels, vaults, and stairways map centuries of shifting rule, faith, and ceremony—always in dialogue with the city below.

Table of Contents

Hillfort origins & early princes

Prague Castle began as a strategic hillfort in the 9th century, a wooden‑and‑earthwork stronghold overlooking bends of the Vltava. Early Přemyslid princes chose this high spur for defense, visibility, and control of movement along the river valley—an elevated stage where power could be seen and signaled.

What started as timber palisades and simple courtyards gradually gathered stone chapels, princely residences, and service lanes. The pattern—ceremony near the crest, craft and supply along the flanks—set a rhythm the castle keeps to this day, even as materials, rulers, and rituals changed.

Gothic ambition under Charles IV

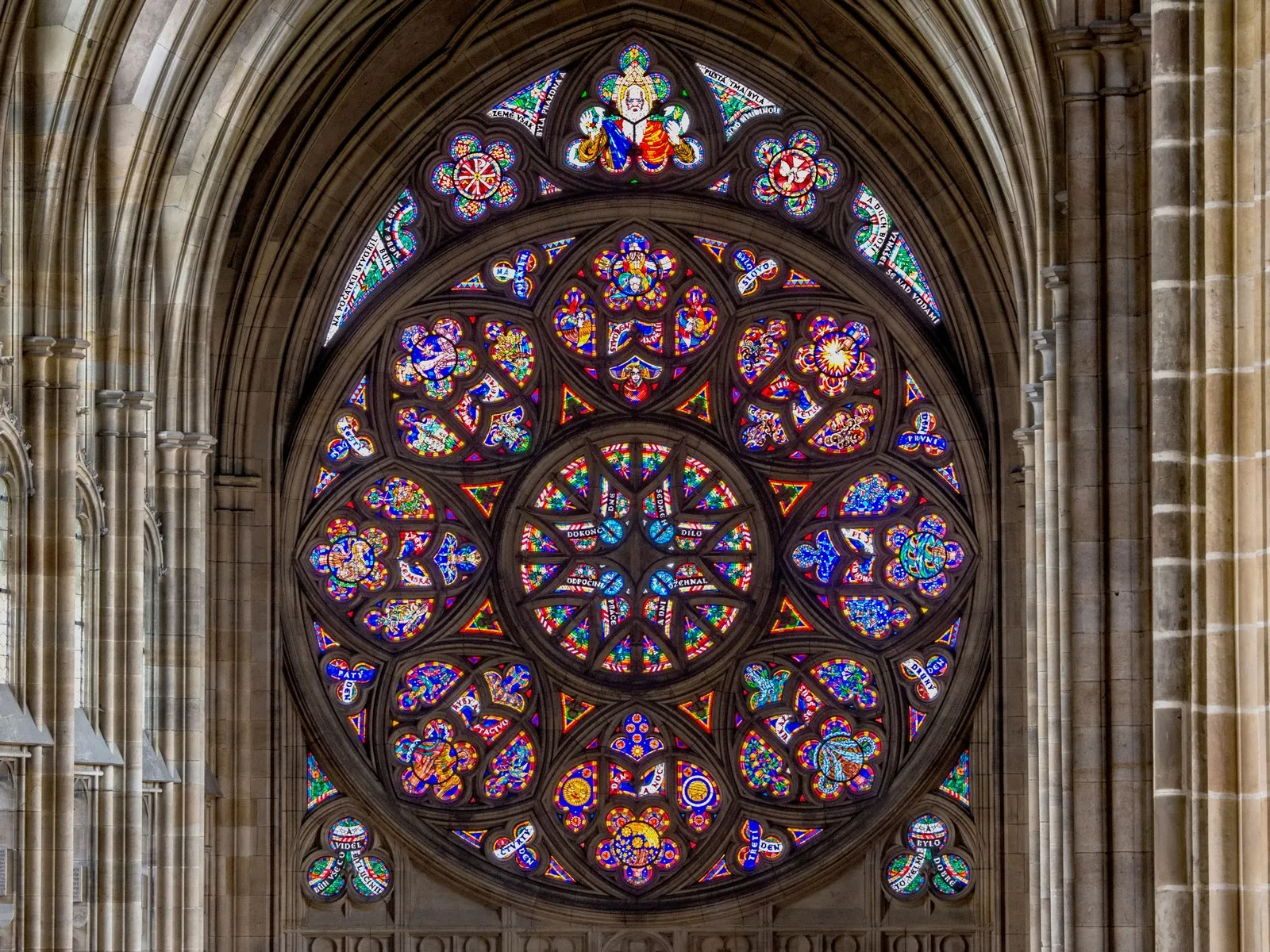

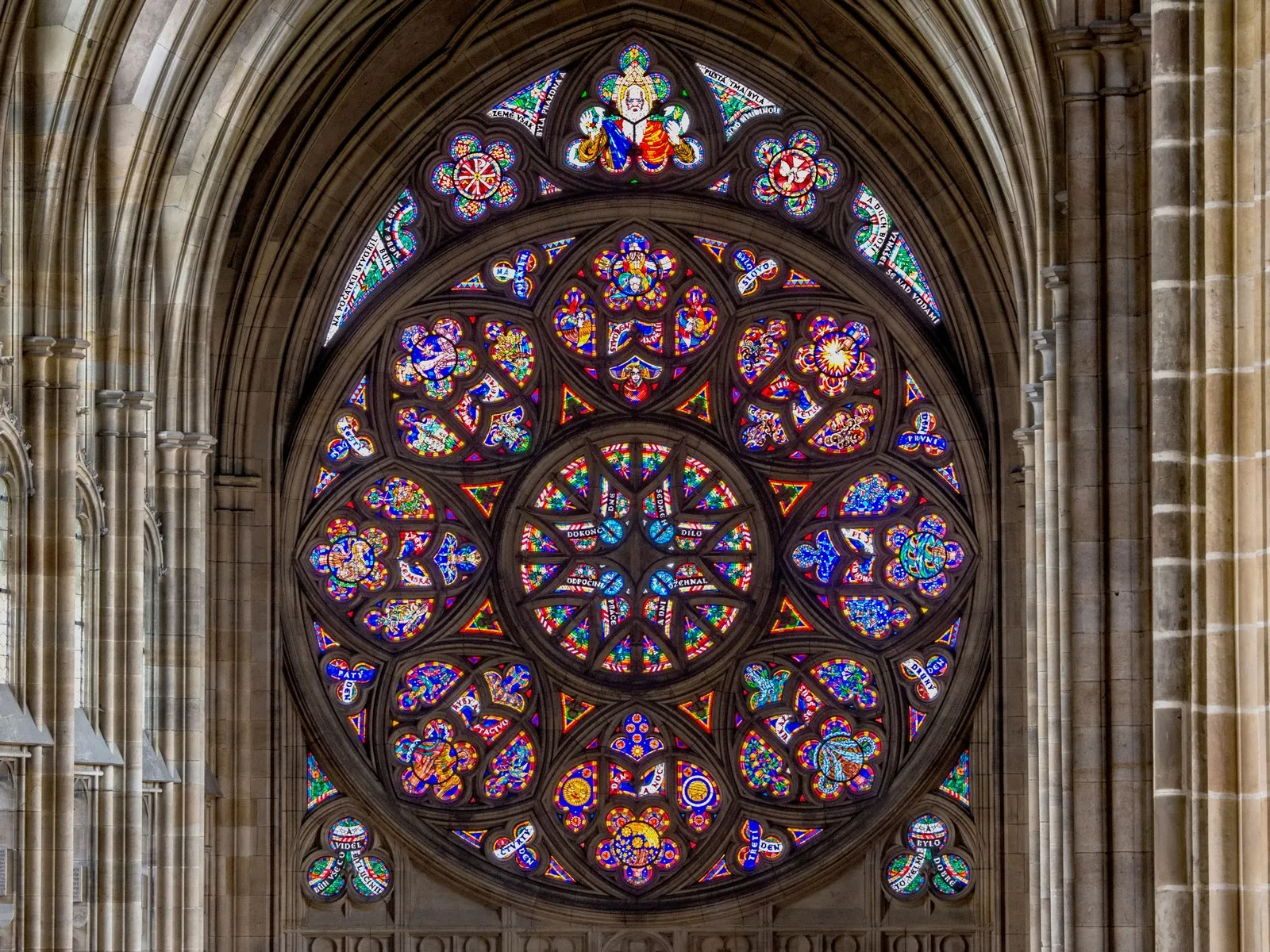

The 14th century under Charles IV transformed the skyline. St. Vitus Cathedral rose with pointed arches and ribbed vaults; colored glass washed the stone in stories of saints and rulers. Gothic wasn’t just an aesthetic, but a policy: to crown Prague as imperial capital, its buildings had to speak Europe’s grand language of height and light.

Cathedral workshops hummed—masons tracing geometry, glaziers firing pigments, carvers setting foliage in stone. The site knit faith with politics: coronations, royal burials, and reliquaries placed Prague’s destiny beneath vaulted canopies that still draw the eye upward.

Palace halls & civic spectacle

The Old Royal Palace added one of Central Europe’s great rooms: Vladislav Hall, a sweeping late‑Gothic space whose stone ribs seem to billow like sails. Markets, feasts, coronation banquets, and even indoor horse displays unfolded here, knitting court ritual with civic life.

Stairways wide enough for mounted entries, chambers for audience and judgment, and balconies for proclamation turned architecture into theater—law, ceremony, and rumor all had places to stand and be heard.

Renaissance and Baroque layers

Habsburg rule brought Renaissance symmetry and later Baroque pomp—arcades, state apartments, and ordered gardens signaled a different mode of power, less martial, more ceremonial and administrative.

Instead of erasing the past, new wings leaned into it. Gothic gables sit near Renaissance loggias; a Baroque facade frames medieval cores. The castle reads like a palimpsest, each era’s handwriting legible beneath the next.

Courtly life, ritual, and rumor

Processions stitched calendar to stone—coronations, Te Deums, envoys with gifts, and legal pronouncements from balconies. Rumor moved fast too, from chambers to taverns in Malá Strana, because the castle’s decisions touched every craft and stall below.

Gardens softened the protocol—lilies and the Singing Fountain in the Royal Garden, orchard air on terraces, and quiet paths for unguarded conversation. Ceremony needs breath; the gardens supply it.

Stone, glass, and craft guilds

Guilds coordinated masons, sculptors, carpenters, metalworkers, and glaziers. Templates of circles and triangles guided ribs and tracery; furnaces fixed color into glass; chisels taught leaves to curl from limestone.

Restorers today trace tool marks and mortar recipes, reading the building like a workbook. Conservation is collaboration across centuries: leave no scar that future hands can’t understand.

Accessibility, comfort, and weather

Slopes, cobbles, and stairs are part of the terrain, but several adapted routes and ramps exist. Official resources outline the smoothest paths through the main courtyards and interiors.

Hilltop weather shifts quickly—carry layers and water. In summer, arcades and garden edges give shade; in winter, interiors offer reprieve before you step back into the breeze.

Conservation & living heritage

Preventive care balances mass visitation with fragile materials—monitoring moisture in vaults, salt in stone, and vibration from footsteps to keep the past audible but intact.

Gardens are living exhibits too—careful irrigation and species choice protect views and historic layouts while adapting to changing climates.

Castle on screen & in symbol

The castle’s silhouette—spires and battlements—became a city emblem and frequent film backdrop. Cinematic light loves Prague: mist in morning courtyards, lanterns along lanes at dusk.

Photos often chase contrasts: the cathedral’s height against humble cottages, or gilded altars after rain‑washed stone. Symbol and story converge here.

Planning a route with context

Try a time‑layer route: begin with St. George’s Romanesque calm, then the Gothic lift of St. Vitus, on to the late‑Gothic Vladislav Hall, finishing in Renaissance gardens for a soft landing.

Watch for material shifts—stone tooling, glass tones, vault geometries, and hardware on doors—your best clues to era and intention.

Prague’s trade, power, and river

The Vltava isn’t just scenery—it bound trade routes, mills, and markets to the castle’s decisions. Wealth flowed from river to court, and back out as commissions for craft and building.

Streets around the hill absorbed change: new parishes, guild halls, and universities rose under the castle’s gaze. Power sat above, but the city’s hum wrote the footnotes.

Nearby complementary sites

Stroll to Loreto Square, wander Malá Strana’s lanes, cross the Charles Bridge at twilight, or climb the Petřín Lookout for a mirrored skyline.

Pair the castle with Old Town’s civic monuments and Jewish Quarter histories for a well‑balanced Prague story.

Enduring legacy of the Castle

Prague Castle condenses a millennium of European turns—dynasties, devotions, and design languages—into one lived‑in hill.

Its legacy is practical as well as poetic: a working seat of state that still lets the public thread the same courtyards as kings, canons, and craftsmen.

Table of Contents

Hillfort origins & early princes

Prague Castle began as a strategic hillfort in the 9th century, a wooden‑and‑earthwork stronghold overlooking bends of the Vltava. Early Přemyslid princes chose this high spur for defense, visibility, and control of movement along the river valley—an elevated stage where power could be seen and signaled.

What started as timber palisades and simple courtyards gradually gathered stone chapels, princely residences, and service lanes. The pattern—ceremony near the crest, craft and supply along the flanks—set a rhythm the castle keeps to this day, even as materials, rulers, and rituals changed.

Gothic ambition under Charles IV

The 14th century under Charles IV transformed the skyline. St. Vitus Cathedral rose with pointed arches and ribbed vaults; colored glass washed the stone in stories of saints and rulers. Gothic wasn’t just an aesthetic, but a policy: to crown Prague as imperial capital, its buildings had to speak Europe’s grand language of height and light.

Cathedral workshops hummed—masons tracing geometry, glaziers firing pigments, carvers setting foliage in stone. The site knit faith with politics: coronations, royal burials, and reliquaries placed Prague’s destiny beneath vaulted canopies that still draw the eye upward.

Palace halls & civic spectacle

The Old Royal Palace added one of Central Europe’s great rooms: Vladislav Hall, a sweeping late‑Gothic space whose stone ribs seem to billow like sails. Markets, feasts, coronation banquets, and even indoor horse displays unfolded here, knitting court ritual with civic life.

Stairways wide enough for mounted entries, chambers for audience and judgment, and balconies for proclamation turned architecture into theater—law, ceremony, and rumor all had places to stand and be heard.

Renaissance and Baroque layers

Habsburg rule brought Renaissance symmetry and later Baroque pomp—arcades, state apartments, and ordered gardens signaled a different mode of power, less martial, more ceremonial and administrative.

Instead of erasing the past, new wings leaned into it. Gothic gables sit near Renaissance loggias; a Baroque facade frames medieval cores. The castle reads like a palimpsest, each era’s handwriting legible beneath the next.

Courtly life, ritual, and rumor

Processions stitched calendar to stone—coronations, Te Deums, envoys with gifts, and legal pronouncements from balconies. Rumor moved fast too, from chambers to taverns in Malá Strana, because the castle’s decisions touched every craft and stall below.

Gardens softened the protocol—lilies and the Singing Fountain in the Royal Garden, orchard air on terraces, and quiet paths for unguarded conversation. Ceremony needs breath; the gardens supply it.

Stone, glass, and craft guilds

Guilds coordinated masons, sculptors, carpenters, metalworkers, and glaziers. Templates of circles and triangles guided ribs and tracery; furnaces fixed color into glass; chisels taught leaves to curl from limestone.

Restorers today trace tool marks and mortar recipes, reading the building like a workbook. Conservation is collaboration across centuries: leave no scar that future hands can’t understand.

Accessibility, comfort, and weather

Slopes, cobbles, and stairs are part of the terrain, but several adapted routes and ramps exist. Official resources outline the smoothest paths through the main courtyards and interiors.

Hilltop weather shifts quickly—carry layers and water. In summer, arcades and garden edges give shade; in winter, interiors offer reprieve before you step back into the breeze.

Conservation & living heritage

Preventive care balances mass visitation with fragile materials—monitoring moisture in vaults, salt in stone, and vibration from footsteps to keep the past audible but intact.

Gardens are living exhibits too—careful irrigation and species choice protect views and historic layouts while adapting to changing climates.

Castle on screen & in symbol

The castle’s silhouette—spires and battlements—became a city emblem and frequent film backdrop. Cinematic light loves Prague: mist in morning courtyards, lanterns along lanes at dusk.

Photos often chase contrasts: the cathedral’s height against humble cottages, or gilded altars after rain‑washed stone. Symbol and story converge here.

Planning a route with context

Try a time‑layer route: begin with St. George’s Romanesque calm, then the Gothic lift of St. Vitus, on to the late‑Gothic Vladislav Hall, finishing in Renaissance gardens for a soft landing.

Watch for material shifts—stone tooling, glass tones, vault geometries, and hardware on doors—your best clues to era and intention.

Prague’s trade, power, and river

The Vltava isn’t just scenery—it bound trade routes, mills, and markets to the castle’s decisions. Wealth flowed from river to court, and back out as commissions for craft and building.

Streets around the hill absorbed change: new parishes, guild halls, and universities rose under the castle’s gaze. Power sat above, but the city’s hum wrote the footnotes.

Nearby complementary sites

Stroll to Loreto Square, wander Malá Strana’s lanes, cross the Charles Bridge at twilight, or climb the Petřín Lookout for a mirrored skyline.

Pair the castle with Old Town’s civic monuments and Jewish Quarter histories for a well‑balanced Prague story.

Enduring legacy of the Castle

Prague Castle condenses a millennium of European turns—dynasties, devotions, and design languages—into one lived‑in hill.

Its legacy is practical as well as poetic: a working seat of state that still lets the public thread the same courtyards as kings, canons, and craftsmen.